Yōkai: Onryō (怨霊 vengeful spirit)

Onryō can inflict injury, bring about the demise of their enemies, and even unleash catastrophic natural disasters. They are considered the most feared and dreaded type of yūrei, the ghosts of Japan.

In the world of Japanese folklore and literature, the concept of onryō, often referred to as “vengeful spirits,” holds a prominent place. These spirits are believed to possess the ability to unleash harm upon the living, seeking retribution for the injustices they suffered during their earthly existence. With their powerful wrath, onryō can inflict injury, bring about the demise of their enemies, and even unleash catastrophic natural disasters. They are considered the most feared and dreaded type of yūrei, the ghosts of Japan.

While similar to goryō, another spiritual entity associated with vengeance, onryō specifically embody a fierce and vengeful nature. Their purpose is to right the wrongs inflicted upon them, taking vengeance on those who caused their suffering. The manifestation of an onryō can result from various circumstances, such as untimely deaths, betrayal, or deep-rooted grudges. These spirits are driven by an insatiable desire for justice and restitution.

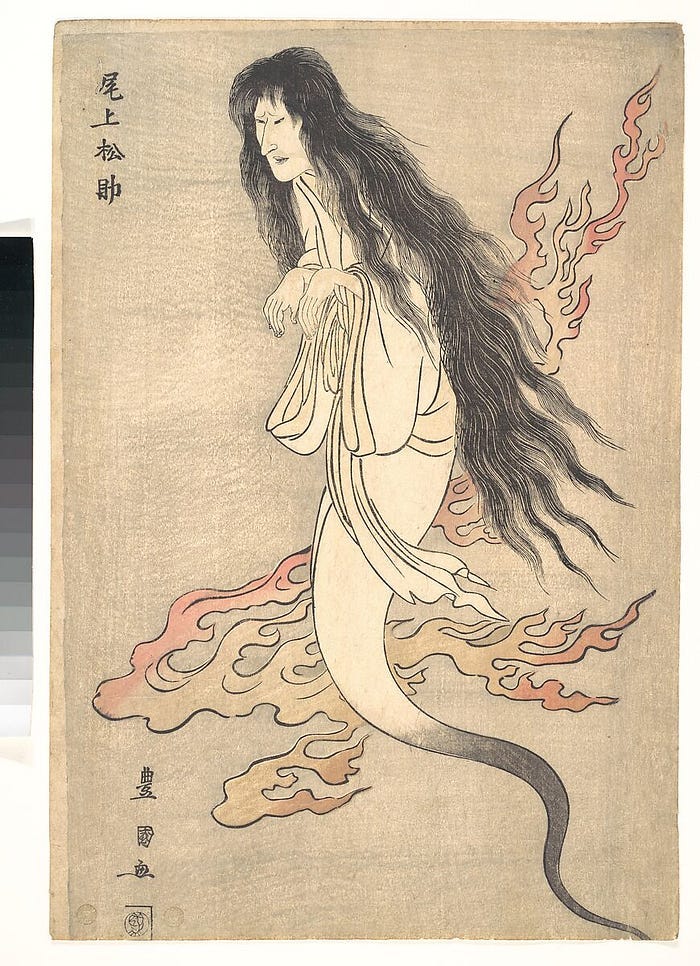

The tales of onryō resonate throughout Japanese culture, appearing in ancient folklore, literature, and theatrical performances. Their presence is characterized by distinct traits, often depicted with long, flowing hair that obscures their faces and wearing white garments reminiscent of burial attire. It is said that they lack hands and feet, floating eerily just above the ground.

The onryō’s influence extends beyond the mortal realm, as they possess supernatural abilities to torment their adversaries. Through haunting visions and the manipulation of fate, they bring misery and suffering to those who have wronged them. The onryō’s wrath knows no bounds, and their vengeance can extend to entire communities, inflicting widespread devastation and calamity.

Yet, amid the terror and malevolence associated with onryō, there is a deeper exploration of the human condition. These spirits represent the unresolved pain and anguish harbored within individuals, embodying the consequences of unchecked emotions and the unaddressed wounds of the past. They serve as cautionary reminders of the importance of empathy, compassion, and the pursuit of reconciliation to avoid succumbing to a path of vengeful spirits.

Throughout generations, the legends of onryō have endured, captivating audiences with their chilling tales. These stories serve as a reflection of the complex and multifaceted nature of the human spirit, reminding us of the profound impact our actions can have on others and the importance of seeking redemption and healing in the face of turmoil. The legacy of the onryō continues to fascinate and intrigue, inviting contemplation on the delicate balance between justice, vengeance, and the power of forgiveness.

The Origin

The origins of onryō remain shrouded in mystery, yet their existence can be traced back to ancient times, particularly to the 8th century in Japan. It was during this period that a belief emerged in the powerful and wrathful souls of the deceased, capable of influencing or inflicting harm upon the living. This belief laid the foundation for the concept of onryō.

One of the earliest recorded instances of an onryō cult centers around Prince Nagaya, who met his demise in 729. This cult formed around the idea that the prince’s restless spirit sought vengeance and could bring misfortune upon those who crossed its path. As time went on, tales of onryō became intertwined with historical events and legends, cementing their status as fearsome supernatural entities.

A significant account referencing the influence of an onryō on the living can be found in the chronicle Shoku Nihongi, compiled in 797. The chronicle recounts the story of Fujiwara Hirotsugu, a noble who perished during the ill-fated Fujiwara no Hirotsugu Rebellion. According to the chronicle, Hirotsugu’s soul was believed to have inflicted harm upon Genbō, a prominent priest, ultimately leading to his demise. This historical event marked one of the earliest recorded instances of an onryō spirit affecting the health and well-being of a living individual.

The concept of onryō evolved and became deeply ingrained in Japanese culture, finding expression in literature, art, and theatrical performances. Tales of onryō often featured women or children who were wronged in their past lives, seeking revenge against those who caused them harm. These vengeful spirits were depicted with long, disheveled hair, pale skin, and a hauntingly ethereal presence.

The onryō’s ability to exact vengeance was not limited to individuals but extended to wreaking havoc on a larger scale. They were believed to possess the power to cause calamities such as earthquakes and tsunamis, inflicting widespread destruction upon communities and landscapes.

The legend of onryō serves as a reflection of the human psyche, exploring themes of unresolved grievances, the consequences of injustice, and the desire for retribution. It delves into the depths of human emotions and the capacity for anger and sorrow to transcend death itself. Through these stories, the onryō becomes a cautionary symbol, urging individuals to address conflicts and seek resolution before they manifest into vengeful forces.

Today, the legacy of onryō endures, captivating the imagination of audiences worldwide. These tales continue to provide insights into the complexities of the human spirit and serve as a reminder of the lasting impact our actions can have, both in life and beyond. The enigmatic nature of onryō keeps their legend alive, inviting contemplation on the enduring power of unresolved emotions and the importance of finding peace and reconciliation.

Characteristic

In the realm of Japanese folklore, the onryō, driven by their deep-seated thirst for vengeance, possessed the ability to unleash not only death upon their enemies but also to wreak havoc on the natural world. It was believed that these vengeful spirits could bring forth calamities such as earthquakes, fires, storms, droughts, famines, and pestilence as a means of retribution. This form of supernatural vengeance, known as tatari, was deeply ingrained in the cultural consciousness.

One notable tale highlighting the devastating power of the onryō involves the clash between Prince Sawara and Emperor Kanmu. The emperor accused his brother, Prince Sawara, of plotting against him in a bid for the throne. Although Prince Sawara’s death resulted from self-imposed exile and fasting, the emperor feared the wrath of his brother’s spirit. To escape its potential consequences, Emperor Kanmu decided to relocate the capital from Nagaoka-kyō to Kyoto. However, even this drastic measure did not entirely appease the vengeful spirit. In an attempt to lift the curse, the emperor conducted Buddhist rituals and posthumously granted Prince Sawara the title of emperor as a gesture of respect.

Another well-known instance of attempting to appease an onryō spirit is the case of Sugawara no Michizane. After being politically disgraced and dying in exile, Michizane’s spirit was believed to have caused the swift demise of those who had wronged him and even brought about natural disasters, particularly lightning damage. In order to pacify the wrathful spirit, the court sought to rectify the situation by restoring Michizane’s former rank and position. Eventually, Michizane was deified and became the focal point of the Tenjin cult, with Tenman-gū shrines erected in his honor.

These tales of appeasement and the consequences of invoking the wrath of the onryō serve as cautionary reminders of the potent forces that lay dormant within the spirit world. They illustrate the deeply rooted belief in the interconnectedness of human actions and natural phenomena, as well as the repercussions of seeking revenge. These legends also reflect the cultural importance placed on restoring harmony and balance, highlighting the rituals and gestures of respect employed to mitigate the wrath of vengeful spirits.

While the belief in onryō and their ability to influence the world may have waned in modern times, their stories continue to resonate, offering insights into the intricate relationship between humanity and the supernatural. They serve as a testament to the enduring power of folklore and the rich tapestry of beliefs that have shaped Japan’s cultural landscape.

Physical appearance

Throughout traditional Japanese culture, onryō and other yūrei (ghosts) were not defined by a specific appearance. However, during the Edo period when Kabuki theater gained popularity, a distinctive costume was developed to visually represent these supernatural entities.

Kabuki, known for its visually captivating performances, employed a system of visual cues to instantly convey characters and their emotions to the audience. When portraying a ghost, actors would don a specific costume consisting of three key elements:

A white burial kimono, known as shiroshōzoku or shinishōzoku, symbolizing the attire worn by the deceased.

Long, disheveled black hair, left wild and unkempt. This characteristic hairstyle was intended to create an eerie and unsettling appearance.

Face make-up featuring a white foundation called oshiroi, which provided a ghostly complexion. Additionally, the actors would use face paintings known as kumadori to accentuate specific emotions. The onryō characters often had blue shadow markings, referred to as aiguma or “indigo fringe,” reminiscent of the way villains are depicted in Kabuki make-up artistry.

These distinctive visual elements of the ghost costume in Kabuki theater allowed the audience to immediately recognize the presence of an onryō or other spectral beings on stage. The combination of the white burial kimono, long black hair, and intricate face make-up enhanced the theatrical experience, heightening the eerie and supernatural atmosphere.

By incorporating these visual cues, Kabuki brought the world of ghosts and vengeful spirits to life, captivating audiences with its dramatic portrayals and evocative aesthetics. The ghostly costume became an iconic representation of onryō in Japanese culture and continues to be recognized as a powerful symbol of the supernatural in theatrical performances and popular media.

The Legend

One of the most renowned onryō figures is Oiwa, featured in the chilling tale known as Yotsuya Kaidan. Unlike many onryō stories where the husband is the victim, Oiwa’s vengeance takes a psychological toll on her unharmed husband.

How a Man’s Wife Became a Vengeful Ghost and How Her Malignity Was Diverted by a Master of Divination

In this medieval story from the collection Konjaku Monogatarishū, a husband discovers his abandoned wife dead, her hair untouched and her bones intact. Fearing the wrath of her vengeful spirit, he seeks assistance from a diviner, an onmyōji. The husband must face a harrowing trial by gripping her hair and riding upon her lifeless body. As he endures this eerie task, Oiwa’s ghost complains about the burden and ventures out in search of him. However, after a fruitless day, she returns, allowing the diviner to complete her exorcism with a powerful incantation.

Of a Promise Broken

This tale, recorded by Lafcadio Hearn and originating from the Izumo region, tells the story of a samurai who makes a solemn vow to his dying wife, promising never to remarry. Sadly, he breaks his pledge and enters into a new marriage. Enraged by his betrayal, the ghost of his deceased wife appears, first as a warning and then as a murderous entity. The ghost violently tears off the head of the young bride. The watchmen, previously put to sleep by the ghost’s supernatural powers, awaken and pursue the apparition. With a swift slash of the sword and the recitation of Buddhist prayers, they succeed in destroying the vengeful spirit.

These tales of Oiwa and the broken promises that fueled her wrath demonstrate the chilling power of onryō. Their haunting presence lingers in Japanese folklore, serving as cautionary tales of the consequences that arise from betrayal, broken vows, and the anger of the departed. These stories continue to captivate and terrify audiences, showcasing the enduring fascination with onryō and their enduring place in Japanese ghost lore.

Popular Culture

The onryō archetype has become a prominent presence in the J-Horror genre, exemplified by iconic characters such as Sadako Yamamura from the Ring franchise and Kayako Saeki from the Ju-On franchise. These female characters, who were victims of injustice in life, return as onryō to unleash terror upon the living and seek their own rebirth.

In the realm of video games, Hisako, also known as the “Eternal Child” or “Everlasting Child,” appears as an onryō in the fighting game Killer Instinct. She met her demise while defending her village and now haunts its ruins, wielding a naginata to exact vengeance upon those who desecrate the sacred site. With her pale white skin and long black hair, she embodies the classic onryō aesthetic.

Cynthia Velasquez, in the ghost form depicted in the survival horror game Silent Hill 4: The Room, bears a striking resemblance to the traditional onryō. Her spectral appearance draws upon the eerie characteristics associated with these vengeful spirits.

In the autumn of 2018, the asymmetrical horror game Dead by Daylight introduced Rin Yamaoka, known as The Spirit, in their Shattered Bloodline chapter DLC. The Spirit is an onryō who returns from the afterlife after enduring a brutal murder at the hands of her father. With her ethereal presence, she embodies the wrath and vengeance typical of onryō figures.

These diverse examples from various forms of media showcase the enduring fascination with onryō and their portrayal as powerful, vengeful entities. From movies to video games, their haunting presence continues to captivate audiences and instill a sense of dread, solidifying their status as icons in the realm of horror.

©Emika Oka

Thank you for reading this.

Your support holds immense significance for a disabled neurodivergent.

If you’d like to show your support, you can consider buying me a coffee here. My collection of eBooks and classic titles is available here. Your kindness is greatly appreciated.

Source

怨霊 - Wikipedia

日本の怨霊一覧!日本三大怨霊とは?怨霊とはどんな意味!? – おししょみの雑学部屋 (oshishomi.com)

【日本三大怨霊まとめ】簡単にわかりやすく解説!!菅原道真・平将門・崇徳院について | 日本史事典.com|受験生のための日本史ポータルサイト (nihonsi-jiten.com)